The Abwehr And The Jews

- Get link

- X

- Other Apps

The Abwehr And The Jews - M.N.: This is a very important story. | Michael Novakhov on the New Abwehr hypothesis of the Operation Trump

M.N.: This is a very important story. It confirms my impressions, formed earlier, that the Orthodox Judaism in general, and its various offshoots , such as "Chabad Lubavitch" and other "Hasidic movements", just like the State of Israel itself (God bless it), are nothing less and nothing more than the creations of the Abwehr and the New Abwehr (after WW2), which themselves were and are predominantly half or part Jewish, especially in their "top heavy" leadership circles, including Canaris himself and most of his commanding officers, as exemplified by this particular one described in this article.

It was a historically formed and a historically determined circumstance: the ethnically German junkers looked down upon the Intelligence work which, as they felt, was not compatible with their ideal of the "honest military service", and they gladly or by necessity gave this area to the Jews and part Jews to manage. Another half of this formula might have been in the objective military observations that the smart, creative, ambitious, and quite German-wise patriotic Jews were simply much better and more efficient in this area, and they accepted and practiced this observation as the rule of their science and arts of wars and espionage.

For the half and part Jewish Abwehr officers this "half and half" became their ideal and their elaborate "philosophy": the fusion of the Germanic and the Hebrew Spirits and their best embodiment and representations (in the high Abwehr officers, of course).

It also included the criteria for the personnel selection; most of the Abwehr high officers do LOOK half or part Jewish.

This point is very important for the understanding of the Abwehr's and the New Abwehr's psychology, outlook, and the nature, the character, and the distinguishing, the "diagnostic" features of their operations.

The New Abwehr apparently, influences and manipulates the Orthodox Judaic movements, especially their pet project, the "Chabad Lubavitch" and other "Hasidic movements" quite heavily and almost absolutely invisibly, masking and advertising their "Putin connection" as the quite efficient, convenient, and convincing cover.

These issues need the sophisticated and in-depth research.

With regard to Trump Investigations, this assumption, or the working hypothesis, as described above, has the direct bearing and is a factor in understanding the Sphinx The Regent Jared Kushner, his family, their origins, and the origins of their wealth.

The so called "Bielski Partisans" absolutely could not exist, function, and survive (quite nicely, with the trainloads of the robbed Nazi Gold and jewelry, which they later invested in the US real estate and other successful business ventures-rackets) without the overt or tacit approval and consent from the Abwehr which controlled everything on the occupied territories.

The Kushner Crime Family was the tool: kapos and the enforcers for the Abwehr. They became their money launderes and money managers after the WW2, when Abwehr moved them to the US.

The Trump Crime Family was the long term Abwehr assets, starting from Frederich Trump, Donald's grandfather, who run the bordellos for them, and including Fred Trump, Donald's father who built the "economy" housing for the newly arrived Abwehr agents, mixed into the mass of the legitimate refugees, and who also became the money launderer and the money manager for the Abwehr and the New Abwehr.

Recently they (the New Abwehr planners) decided to merge these two families into a single Trump-Kushner Crime Family, in what was clearly the arranged marriage between Jared and Ivanka, in preparation and as the first step towards Operation Trump. It was helped, as the apparent second step in this arrangement, by Wendi Deng the "Chinese spy", as alleged and circulated by Rupert Murdoch, her husband at the time. Both of them, just as, hypothetically, the FOX News Corporation were (and are?) heavily influenced by the New Abwehr. For Murdoch this proclivity apparently also runs in a family. This is the apparent pattern of this prudent way of family recruitment; universally, and for the Abwehr in particular.

This aspect is also important for the understanding of the role that Felix Sater and his "Chabad" sect played in the "Trump - Russia Affair".

This thesis about the connection between the Orthodox Judaism and Abwehr is also consistent with the "Abwehr Diagnostic Triad" which was formulated by me earlier, as consisting of:

1) Judeophobia (as the psychological product of these described above circumstances: the Abwehr half Jews were the GOOD (half) JEWS, all the rest were "very bad, sick, and contaminating" Jews),

2) Homophobia (the so called "Internalized Homophobia", stemming from the personal aspects of the Abwehr leadership and reflecting the general, very permissive attitude towards homosexuality among the German military circles before and especially in the aftermath of the WW1), and

3) the specific Austrophobia or the so called Anti-Austrian sentiment (distrust and hate of all things Austrian), which stems from the Austro - Prussian War of 1866 and from the Austria–Prussia rivalry.

In the "Trump Affair", the Austrophobia aspect is expressed by the New Abwehr planners in the concept of the "decadent and dishonest, not to be trusted", part Jewish, Hapsburg Group, and this circumstance can be viewed as the particularly "telling", or highly suggestive and indicative, "pathognomonic", of the Abwehr operations.

Michael Novakhov

2.13.19

See Also:

________________________________________________

The RMS Aquitania. (Library of Congress)

In my aunt’s house, in the bedroom where

I’ve often slept, there’s a framed photo of a ship’s manifest that I love to stare at. The ship was the RMS Aquitania, a Cunard ocean liner with an inky-black hull that was famous for its four smokestacks; its picture hangs in the bedroom, too. I can spend long minutes looking at these photos, first the ship, then the manifest, with its clutter of blocky print that draws my eyes up, down, and across the page until they finally settle on the name I’m always looking for: Ozcar Ratowzer. The print tells me that he was a worker from the town of Bialystok in Poland. If I trace down the column labeled “race or people,” I come to the word “Hebrew.”1

Ozcar Ratowzer, also known as Osher, was my grandfather. The manifest lists him as being 16, but my family believes he was closer to 19 or 20 when he boarded the Aquitania in Southampton, England, on October 23, 1920, and began his third-class voyage across the Atlantic. The journey took seven days, finally depositing him at Ellis Island, America’s “Golden Door,” the gateway to a world without pogromsor hunger or the horror of world war. There, he would almost certainly have been met by an assembly line of doctors and inspectors, who would have poked and peered at him, pried and questioned until, content with what they’d found, they would have sent him on his way with his handful of old-world possessions and the shards of a new identity. He would soon become known as Harry Ratner.2

My grandfather’s journey has always moved me, filled me with overwhelming gratitude and awe, not least because I’m aware how differently it might have turned out. Ozcar’s passage to this country was far from guaranteed. A Jewish kid of conscription age, he was barred from leaving Poland legally, meaning that he and one of his older brothers, Leiser, were forced to slip over the border with Germany dressed as cattle herders, then hide in a barn overnight, buried in haystacks. Their first attempt failed: My grandfather was caught by a bunch of pitchfork-wielding German guards and sent back across the border. His second attempt was more successful, but once in Germany, he and his brother ran into a second hurdle: They were carrying fake German passports, and, family accounts suggest, the American consul had no intention of honoring them. It was only after the intercession of their oldest brother, Kalman, a Bolshevik sympathizer turned American citizen and Freemason, that the consul agreed to grant them passage to the United States. (According to family lore, the consul was also a Freemason.)3

The brothers arrived safely on Ellis Island on October 30, 1920, and soon made their way to Cleveland. The rest of the family—their parents and six of their siblings—arrived on the RMS Caronia two months later, though their journey ended less happily. My grandfather’s 9-year-old brother, Joseph, had fallen ill on the boat to America, and he died just a few weeks after reaching this country.4

Still, the family was lucky. Although they didn’t know it at the time, the United States was about to begin slamming the door shut on immigrants just like them—and it would keep that door sealed for several decades.5

* * *6

My grandfather’s near-miss has haunted me

for years—what if he hadn’t made it to this country when he did?—but the thought has been relentless these last few months. Ever since Donald Trump’s upset victory, I’ve had the sickening sense that history is reversing itself, whipping us back to a time when a noxious, state-sponsored xenophobia gravely imperiled millions of would-be Americans. It’s not that I have any illusions about the Obama administration, with its mass deportations and failure to welcome even a fractional number of Syrian refugees. But with Trump’s ascendancy—with his plans to ban Syrian refugees, suspend immigration from majority-Muslim countries, round up undocumented immigrants, and begin construction of a “physical wall”—we seem to be witnessing the rise of something at once utterly distinct and hauntingly familiar: a revived anti-immigrant regime, a nativist moment not unlike the one that seized this country a century ago.7

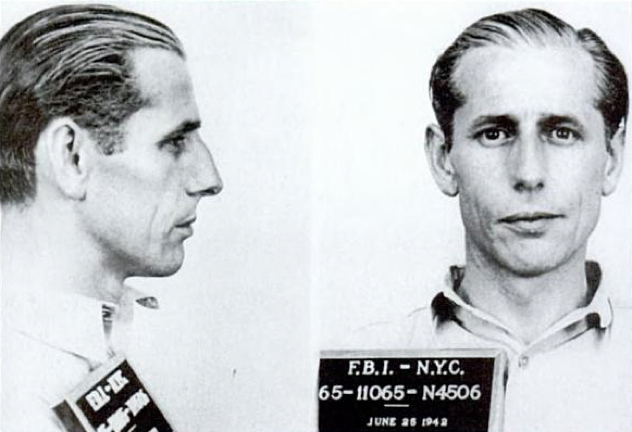

Osher Ratowczer, later Harry Ratner, in Danzig, Germany in 1920, before heading to the United States.

The parallels between that earlier period and today often get lost amid more provocative historical comparisons—to Germany in 1933, for example. Nonetheless, it’s worth considering this other quintessentially American moment, which began in the years before my grandfather made his way west and which, in the words of historian Alan Kraut, “rang down the curtain on the flexible migration we’d had before.”8

During that tumultuous time, the United States was in the throes of an intense anti-immigrant fervor, stoked by world war, the Russian Revolution, and a budding love affair with eugenics. Anti-Catholicism raged, anti-Semitism simmered, and Americans were gripped by xenophobia. They feared that the masses of Eastern and Southern Europeans streaming into the country would “mongrelize” the nation, undermining its Anglo-Saxon awesomeness with their crude customs and inferior intellects. They fretted that these “undesirables” would remain unassimilated “hyphenates”—part American, part something else—for years to come. They worried that they would “be a drain on the resources of America.” And, perhaps most intriguing, they feared that many of these immigrants—Jews and Italians, in particular—were, in fact, stealth Bolsheviks and radicals seeking to flip the country red from the inside.9

As the authors of a famous 1920 congressional report recommending a “temporary suspension of immigration” wrote of the Jews then living in Poland: “It is impossible to overestimate the peril of the class of emigrants coming from this part of the world, and every possible care and safeguard should be used to keep out the undesirables.”10

Sound familiar? Although the specific targets have changed, some of the language and much of the vitriol spewed at immigrants some 100 years ago wouldn’t be out of place at one of Trump’s “Make America Great Again” rallies, or tumbling from the mouth of his chosen national-security adviser or attorney general. Then, as now, hypernationalistic figures raged against religious minorities they deemed suspicious, scheming, and potentially disloyal. Then, as now, war abroad stirred up refugee phobias at home. And while there are differences, to be sure—while the past is never simple prelude—then, as is happening again now, the ugly rhetoric quickly gave way to ugly policy.11

Three laws in particular stand out, an unholy trinity that, one by one, narrowed the range of immigrants who were allowed entry via Ellis Island. The first of these laws, the 1917 Immigration Act, attempted to do this by imposing a literacy test on immigrants, barring anyone who couldn’t read, as well as “feeble-minded persons,” “idiots,” “epileptics,” “persons likely to become a public charge,” “anarchists,” and, most stunningly, almost all immigrants from Asia. When this act failed to stanch the flow—when immigrants like my grandfather kept on coming—Congress passed the Emergency Quota Act of 1921, which restricted immigration to a mere 3 percent of the total number of immigrants from any given country already living in the United States in 1910. And when this act proved insufficient? Congress passed the Johnson-Reed Act of 1924, the most stringent of them all, which tightened the quotas to 2 percent of the total immigrants from a given country living here in 1890—a move that effectively slowed immigration to a thin trickle of Nordic and Western Europeans.12

Over the next decades, this new immigration regime would prove devastating for would-be immigrants from a wide swath of countries. For Jews, however, it would prove catastrophic. As the razor wire of fascism tightened around Europe, scores of Jewish men, women, and, yes, children were locked out of this country—and locked into what would soon become a vast killing field. This remained the case even after Kristallnacht shattered any illusions that the Nazis wouldn’t launch a program of organized violence against Jews. And it continued even after the Holocaust began, when the United States not only refused to bend the quotas for fleeing Jews but, under the fierce anti-Semitism of State Department officials like Breckinridge Long, actively found ways to keep them out. Among the more preposterous yet effective arguments: Jewish immigrants were a potential fifth column, possible plants or spies working for the Nazis.13

Even so, there were Jewish immigrants who managed to find their way into the country during these long years of exclusion. Some got lucky and slipped through the narrow bars of the quota system. Others made their way using the same means that desperate thousands use today when they find the borders of this country closed to them: They turned to “surreptitious or illegal entry,” according to the historian Libby Garland, whose book, After They Closed the Gates, tracks the long-overlooked phenomenon of Jewish illegal immigration to the United States. “There were people coming in through unguarded places on the long northern and southern border,” Garland explains, as well as via passenger ships from Cuba and Europe, on which they traveled using forged or illicitly procured documents. “There were networks of people who knew how this worked, and they would coach people.” Garland estimates that “on the order of tens of thousands” of Jewish immigrants might have slipped into the United States this way—namely, illegally—between 1924 and 1965, when the country finally replaced the 1920s restrictions.14

Still, these Jewish migrants represented the minority. The unfortunate majority remained stuck in Europe, waiting as history goose-stepped relentlessly toward them. “It’s very possible that if those laws hadn’t been in place, many of the Jews from Germany, Czechoslovakia, Austria, most of the Jews from Poland, would have been saved,” says Hasia Diner, professor of Hebrew and Judaic studies and history at New York University.15

“I think,” Diner concludes, “that one of the most significant events in modern Jewish history was the stoppage of immigration.”16

* * *17

It’s likely that we’ll never know the number,

or full roster of names, of those refugees who sought and failed to find haven in the United States before and during the Holocaust. Yet one survivor whose story still reverberates is a woman named Rae Kushner. Eloquent and soft-spoken, with a sense of sadness but not rancor, Kushner recorded her story for the Kean College of New Jersey Holocaust Resource Center in 1982. Delivered in a quiet Yiddish-inflected accent, hers is a tale of devastation and tragedy—of a young woman whose family lived in Eastern Europe before the war and, finding that “the door was closed” to the United States and elsewhere, ended up victims of the Nazis. But it’s also a tale of stunning perseverance, in which a teenage girl managed to survive the brutality of the ghetto, the death of half of her immediate family, the white-gloved sadism of her German tormentors, and a year of fear and exposure in the vast Naliboki forest. As she said in the interview: “It’s just miracles that we are alive.”18

I watched the full two-hour sweep of Kushner’s interview for the first time in December, and it has lingered with me ever since. But if it echoes a little more loudly these days, it’s because she also happened to be the grandmother of Jared Kushner, now a senior White House adviser once described as the Trump campaign’s “final decision-maker.” Jared, of course, is also married to Ivanka Trump, which makes him Trump’s son-in-law—and that makes Rae Kushner’s story, with its threads of persecution and exclusion, part of Trump’s own extended-family story, too.19

As Rae Kushner described it in the Kean College interview, her story begins in 1923, when she was born in the small town of Novogrudok, in what was then northern Poland and today is Belarus. The daughter of a furrier—her father owned two stores, which sold men’s hats—Kushner lived what she called “a comfortable life, a quiet life,” with her parents, two sisters, and younger brother. They were not rich, she said, but the children were all educated at private Jewish schools, and her oldest sister even attended college. Although the town’s Jews numbered just 6,000, their world was nonetheless a vital one, a community filled with synagogues, schools, hospitals, and “a nice cultural life.”20

By the mid-1930s, however, the family had begun to sense the first rumblings of trouble. “[W]e felt the anti-Semitism, we felt that it’s coming… something,” Kushner said in the interview. This sense that “something” was brewing was strong enough that a few of her father’s friends left for Palestine and urged her father to “sell everything” and get out, too. The problem, said Kushner, is that “we didn’t have where to run.”21

“You know how hard [it] was to get a visa to Israel…,” she explained, referring, obliquely, to the British policies that restricted Jewish migration to British-controlled Palestine (and to the United Kingdom itself). “To America, very hard. If you sent papers, you’d wait for two, three years till you get a visa at that time.”22

Despite these obstacles, it seems from a brief exchange during the interview that her family did make some sort of effort to get to the United States. “So your family, your father, actually was making attempts in 1935, ’36?” the interviewer, Dr. Sidney Langer, asks Kushner a few minutes into the interview. And she answers, “Yeah, he had a sister here in United States, my father. And we tried…but we couldn’t do nothing.” So they remained in Novogrudok, first as the Soviets invaded and then, in 1941, as the Germans descended on the town and “took us over.”23

Kushner’s description of her family’s years under Nazi occupation is harrowing, and the full scope of what she experienced deserves to be heard in her own words, not simply mediated through a journalist. What can be said, however, is that during several years of unremitting horror, she lost her mother, her older sister, and her younger brother, along with thousands upon thousands of neighbors, friends, and extended family, as the Novogrudok ghetto was whittled from roughly 30,000 Jews to 350. The only way she, her father, and her younger sister managed to survive was by escaping from the ghetto in 1943 through a hand-dug tunnel—one through which all the remaining Jews attempted to crawl to freedom. Many didn’t survive once they made it to the other side, but, miraculously, Kushner, her father, and her sister did—and were eventually rescued by the legendary Jewish partisan Tuvia Bielski. For a year, they lived in the forest with Bielski’s brigade of more than 1,000 Jews until, in the spring of 1944, “he brought us out from the woods.” Novogrudok had been liberated by the Soviets.24

In the Hollywood version of Kushner’s story, this is almost certainly where it would end: with liberation. But for Kushner and her family, like so many other survivors, the trauma lasted several more years, as the family sought a safe place to rebuild their lives. Novogrudok, once again under Soviet control, wasn’t an easy place for Jews—“we had different troubles,” Kushner said—and, moreover, “we were broken, broken down.” So she and her surviving family, along with her soon-to-be-husband Yossel (later, Joseph), decided to leave. But they again faced the problem that had thwarted them a decade earlier when, sensing the rising threat of anti-Semitism, they had contemplated leaving Novogrudok. “Nobody opened the door for us,” Kushner recalled. “Nobody wanted to take us in.”25

Without a country to accept them, the family landed in a displaced-persons camp in Italy, where they lived three or four families to a room for three and a half years. They hoped to get visas to go to the United States, where they had family, but visas were not forthcoming. “We got depressed in the DP camp…,” Kushner stated. “A year, six months—but three and a half years!” It was in this camp, she added, that she gave birth to her first child.26

For this lengthy wait, the Kushners could thank the enduring anti-Semitism of both Eastern and Western European countries, which had little desire to roll out the welcome mat for some of the Nazis’ most beleaguered survivors. But the United States also “shut its doors tight,” says David Nasaw, professor of history at the CUNY Graduate Center, whose current research examines the fate of displaced persons in Germany after the war. Anti-Semitism was certainly part of the equation, but so too were Cold War fantasies about infiltrating communists, among whom Jews—long associated with leftists and radicals—were all too easily lumped. “Congressmen say, over and over again, ‘They’re coming out of Poland, so these Jews are communists or spies,’” Nasaw observes.27

It wasn’t until 1948, when Congress passed the Displaced Persons Act, that the country began cracking open the door to these desperate immigrants. Yet even that gesture was troubled. Larded with a series of cumbersome provisions—including the somewhat inexplicable requirement that 30 percent of the visas go to farmers—the measure was considered so deeply biased against Jewish as well as Catholic immigrants that, even as he signed the act, President Harry Truman denounced it as “flagrantly discriminatory.”28

“For all practical purposes,” Truman wrote in his signing statement, “it must be frankly recognized…that this bill excludes Jewish displaced persons, rather than accepting a fair proportion of them along with other faiths.”29

Despite such hurdles, the Kushners finally did make it to the United States, in 1949. They settled in New York City, worked hard, had a family, made a life for themselves. They pushed on. Still, their difficult and tortuous journey to this country seems to have stayed with Rae Kushner years after she’d put down roots, first in Brooklyn and later in New Jersey. As she lamented toward the end of the Kean College interview, during one of the rare moments her voice rises with a sense of betrayal: “For everybody [there] was a place…but for the Jews, the doors were closed. We never can understand this. Even our good President Roosevelt, how come he kept the doors so closed for us, for such a long time? How come a boat [the SS St. Louis] went for exodus on the water and returned back to be killed? This question I’ll never know, and nobody will give me the answer.”30

* * *31

We don’t need the horrors of the past to

validate the outrages of the present, to tell us that today’s swirl of xenophobia, locked borders, and scapegoating is wrong. Their injustice is self-evident. Still, as a pathologically cynical president resurrects some of the worst demons of this country’s past (and injects new energy into others that never died), history remains a powerful prod for thinking and acting in the present. It’s among the reasons a group of more than 240 Jewish historians, drawing on knowledge both scholarly and personal, vowed in a public letter issued shortly after the election “to resist any attempts to place a vulnerable group in the crosshairs of nativist racism.” And it’s why a dozen Jewish organizations declared in their recent open letter to Donald Trump that they are “committed to defending our country’s identity as a land of refuge.” To their ears, as to so many others, Trump’s attacks on refugees and immigrants smack all too painfully of the past, appealing to an old form of prejudice, resurrected and displaced onto a new era of migrants.32

Harry Ratner at age 6, center, with his brother Max and sister Dora in 1908.

“The blatant discrimination that we’re hearing right now, that’s very much like what we were seeing in 1921,” says Mark Hetfield, the president and CEO of HIAS, a refugee advocacy and resettlement agency that was founded in 1881 to help Jews escaping the pogroms in Russia and Eastern Europe. “I really thought that part of [this country’s] history was behind us and that we would no longer discriminate—certainly not so openly—on the basis of religion, and we wouldn’t turn prejudice into policy like we did in the 1920s. But here we are talking about doing that. I never thought I would see this in my lifetime.”33

Hetfield has been in the refugee trenches for more than a quarter-century, most of the time at HIAS, and his work for the organization has given him a broad lens through which to view today’s Trump-enhanced nativism. Founded as the Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society, HIAS is well known among American Jews as the primary agency that aided Jewish refugees throughout the 20th century—including the Kushners and my own family. In recent years, however, the organization has shifted its focus to aiding refugees from all religions and backgrounds. As Hetfield explains: “The way we describe ourselves is that we used to resettle refugees because they were Jewish; now we resettle refugees because we are Jewish.”34

It’s in the service of this new mission, Hetfield says, that he’s been startled to hear the kind of dehumanizing charges once hurled at Jews now being flung at Muslims, Mexicans, and other refugees and immigrants. “It’s heartbreaking to hear the rhetoric today,” he admits, lamenting the demonization that has cast these groups as a kind of “faceless threat” invading from the south and east.35

When I asked Hetfield how we can properly respond to this moment—and how Jewish experience should inform that response—he was quick to answer, citing both text and history. He spoke of the ancient commandment to “love the stranger as yourself, because you were strangers once in the land of Egypt”—a notion so “integral” that it gets repeated, in one form or another, 36 times in the Torah. And he spoke of the long Jewish experience of seeking refuge in foreign lands. “We have such a long history of having to flee places, such a long history of persecution.… So for us to say, ‘OK, we’re safe, now they can close the doors’—it’s just morally reprehensible to think that way.” His conclusion: “We have to speak out and say it’s unacceptable.”36

Ninety-six years after my grandfather arrived from Bialystok, the story of his journey—of his illegal but impeccably timed emigration from Poland—remains defining yet largely invisible to the world around me. As do so many stories from that era. Once maligned, we descendants of last century’s “undesirable” immigrants are now unquestioned Americans, waltzing through this country as journalists, lawyers, social workers, real-estate developers, and, yes, White House senior advisers. That my grandfather was once part of that class of foreigners dismissed as “filthy,” “un-American,” “abnormally twisted,” “physically deficient,” and “potentially dangerous in their habits”—to quote that infamous 1920 congressional report—has largely been forgotten. The old slurs no longer follow us.37

But they do follow others, slapped on by the president and his supporters, who have smeared today’s immigrants and refugees as “rapists,” “murderers,” carriers of “tremendous infectious disease,” and a “Trojan horse.” And now they’re turning those smears into policy, using them to justify orders that break up families and exclude vast, diverse, and often desperate groups of people. For those keen on exclusion, such justifications will seem convincing. But as surely as the anti-immigrant policies of the early 20th century would prove both baseless and destructive, today’s acts will unleash cruelties and consequences against the would-be immigrants of our own era that we will long regret.38

Read the whole story

· · · · · · · · · · · · ·

| Austro-Prussian War (Seven Weeks' War) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the wars of German unification | ||||||||

Battle of Königgrätz, by Georg Bleibtreu. Oil on canvas, 1869. | ||||||||

| ||||||||

| Belligerents | ||||||||

| ||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | ||||||||

| Strength | ||||||||

637,262[1]

|

517,123[2]

| |||||||

| Casualties and losses | ||||||||

39,990[3]

Breakdown[show]

|

132,414[2]

Breakdown[show]

|

The Austro-Prussian War or Seven Weeks' War (also known as the Unification War,[4] the War of 1866, or the Fraternal War, in Germany as the German War, and also by a variety of other names) was a war fought in 1866 between the Austrian Empire and the Kingdom of Prussia, with each also being aided by various allies within the German Confederation. Prussia had also allied with the Kingdom of Italy, linking this conflict to the Third Independence War of Italian unification. The Austro-Prussian War was part of the wider rivalry between Austria and Prussia, and resulted in Prussian dominance over the German states.

The major result of the war was a shift in power among the German states away from Austrian and towards Prussian hegemony, and impetus towards the unification of all of the northern German statesin a Kleindeutsches Reich that excluded the German Austria. It saw the abolition of the German Confederation and its partial replacement by a North German Confederation that excluded Austria and the other South German states. The war also resulted in the Italian annexation of the Austrian province of Venetia.

Read the whole story

· · · · · · ·

Austria and Prussia had a long-standing conflict and rivalry for supremacy in Central Europe during the 18th and 19th centuries, termed Deutscher Dualismus (German dualism) in the German languagearea. While the rivalry had a military dimension, it was also a race for prestige, and a contest to be seen as the leading political force of the German-speaking peoples.

The rivalry sometimes led to open warfare, from the Silesian Wars and Seven Years' War of the middle 1700s to the conflict's culmination in the Austro-Prussian War of 1866. However, relations were not always hostile; sometimes, both countries were able to cooperate, such as during the Napoleonic Warsand the Second Schleswig War.

Thanks to the late Rabbi Menachem M. Schneerson, Chabad Lubavitch is a well-known and powerful Hasidic movement, with 4,000 emissaries now stationed around the world. But few people know that the rebbe's predecessor, Rabbi Yosef Yitzchak Schneerson, owes his life to a half-Jewish Nazi officer acting under the direct order of the head of the Third Reich's military intelligence agency.

The sixth Lubavitcher Rebbe was hiding in war-torn Warsaw during the days after the German invasion in 1939. After locating the rabbi at the order of Adm. Wilhelm Canaris, the head of the so-called Abwehr, Maj. Ernst Bloch, whose father was Jewish but who had no particular love for Judaism or those who practiced the religion fervently, enabled him to escape to safety in Latvia.

"This operation came about as a result of back-channel diplomatic efforts by the Germans to try and convince the Americans not to enter the war with the British and French against Germany," said Larry Price, whose documentary about this episode, "The Chabad Rebbe and the German Officer," airs tonight (Channel 1, 9:45 P.M. ). According to the Jerusalem-based journalist and filmmaker, the American Chabad community at the time was small in number, but influential enough to save their leader.

"Using their contacts, Chabad managed to get Supreme Court Justice Louis Brandeis involved," the 66-year-old told Haaretz. "Brandeis contacted one of [U.S. President Franklin Delano] Roosevelt's right-hand men, Benjamin Cohen, who influenced Roosevelt to toss the Jewish people a bone. That bone was Rabbi Schneerson."

On Roosevelt's orders

At the time, those demanding that the U.S. government take on a stronger role regarding the fate of European Jewry did so despite "tremendous anti-Semitism in America," Price said. "Roosevelt had to tread lightly and do something, so he thought that perhaps rescuing the rebbe would ameliorate the situation with the Jewish community. The Germans, for their part, thought perhaps they could keep a backdoor channel open with the Americans and prevent them from entering the war."

Releasing one rabbi was a relatively low price to pay, he added. Price's 56-minute documentary details the background of the Schneerson deal and how Bloch and his fellow Abwehr agents accompanied the rabbi and about 20 of his relatives and peers in the first-class cabin of a train from Warsaw to Berlin, using his acting skills to avoid being arrested by suspicious Nazi officers. In the German capital, Schneerson was given over to Latvian diplomats, who brought him to safety in Riga. About a year later he made his way to New York, where he died in 1950. He was succeeded the following year by his son-in-law, Menachem M. Schneerson.

Keep updated: Sign up to our newsletter

Oops. Something went wrong.

Please try again later.

Price, who was born in Chicago and immigrated to Israel in 1971, came across Schneerson's story while working on his previous documentary film, "Hitler's Jewish Soldiers," which tells the story of some of the estimated 150,000 men of Jewish origin who served in the German army during World War II.

"I thought it was a conundrum: Why would the Germans want to send anybody to rescue an ultra-Orthodox Jew from the Germans? It's a very unique story," Price said.

Read the whole story

· · ·

Next Page of Stories

Loading...

Page 2

Read the whole story

· · · ·

Next Page of Stories

Loading...

Page 3

Six Nazi spies were executed in DC White supremacists gave them a ...

Washington Post-Jun 24, 2017

“In memory of agents of the German Abwehr,” the engraving began, ... to show the world just how susceptible America was to a Nazi attack, ...

Secrecy and firing squads: Britain's ruthless war on Nazi spies

The Guardian-Aug 28, 2016

They were agents of the Abwehr, the German military intelligence service, and their mission was to reconnoitre England's south coast for the ...

Trouble on the double

Irish Times-Dec 10, 2010

HISTORY: The Devil's Deal: The IRA, Nazi Germany and the Double Life of Jim ... Many of his former comrades emigrated to the US, but O'Donovan ... to the Continent to meet Abwehr (German intelligence) agents in Brussels, ...

At the Hotel Lutetia, reimagining a piece of Parisian history

The Australian Financial Review-Sep 14, 2018

... received the greater part of the survivors of the Nazi concentration camps, glad to ... Bar Josephine, named after the Franco-American performer Josephine Baker, ... It became the headquarters of the Abwehr, the German ...

Los Nazis homenajeados en Washington

EL PAÍS-Jun 25, 2017

Una lápida en la que se leía: “En memoria de los agentes alemanes de Abwehr ejecutados el 8 de agosto, 1942”. Al final del listado de ...

Five Best: Max Boot

Wall Street Journal-Dec 29, 2017

But the risk-averse Americans repeatedly ignored his efforts to connect ... In 1940, Chapman, imprisoned on the Nazi-occupied isle of Jersey, became ... He had MI5 looking after one girlfriend in London while the Abwehr was ...

15 Things You Didn't Know About Coco Chanel

Mental Floss-14 hours ago

... involved enough with the Nazi agenda that she was referred to as Abwehr ... During World War II, Chanel leveraged her Nazi connections and tried to use .... (The seven before him were all born in the American colonies.) ...

New Book Documents Putin's Rise To Power

WBAA-Dec 14, 2015

Proximity to power did nothing to protect his sons from the Nazis; the entire ..... the ranks of the Abwehr, the Nazi military intelligence organization, and .... “Volodya is everything for us,” he told him, using the diminutive form of ...

Read the whole story

· · ·

How extensive and effective were German espionage and sabotage activities against the United States in World War II? To make generalizations is always dangerous, but certain broad conclusions may perhaps be stated at this time, subject to minor corrections in the light of future data that may be uncovered from enemy sources or that is still closely held by United States or Allied agencies for security reasons. On the side of the enemy's activity it is well-established that from a period before Pearl Harbor until the very end of the war Germany engaged in intensive efforts to obtain military, economic, and political information from the United States. In furtherance of this effort she recruited numerous secret agents to operate within the United States and established extensive espionage networks in other countries of the Western Hemisphere. In the field of attempted sabotage the activity was not comparable; the failure of the large-scale mission entrusted to the eight saboteurs who landed on the East coast in June 1942 appears to have discouraged further efforts in this direction. The German record of accomplishment did not measure up to the effort expended. As far as is known there was no enemy inspired act of sabotage within the United States during the war. On the espionage side, while Germany did from time to time obtain information relating to war production, shipping, and technical advances, it was almost always too late, too inaccurate, or too generalized to be of direct military value. It is possible that in early 1942 Germany did obtain some information that assisted in locating submarine targets, although this has not as yet been finally determined; but on the whole, after Pearl Harbor, German espionage against the United States failed to produce the information required by the High Command. This failure was due to a combination of Allied counter-measures and fatal weaknesses on the part of German intelligence itself.

The secret intelligence requirements of the German [Armed Forces] High Command [O.K.W.] under the Third Reich were served by a separate branch of the O.K.W. called the Amt Auslands und Abwehr (commonly referred to as the Abwehr) independent of the three service commands–Army, Navy, and Air. Each of these three maintained its own intelligence staff for the evaluation and dissemination of information obtained from both open and secret sources; but these staffs conducted no secret intelligence activities themselves. Rather they maintained liaison with the Abwehr to which their special needs for information were made known. These requests the Abwehr endeavored to meet, at the same time being engaged in the task of collecting on a world-wide scale all manner of information which could be of interest to the High Command or the individual services subordinate thereto.

The Abwehr was divided into three basic groups (Abteilung). Abt I was charged with offensive intelligence, including espionage; Abt II with sabotage and subversion; and Abt III with counterintelligence and security. Of these our principal interest lies with Abt I. This was broken down into sections having cognizance respectively over military, naval, air, and economic intelligence, plus certain technical sections. The sections were further broken down into geographical subsections, dealing with particular countries or areas. In addition to the headquarters organization in Berlin the Abwehr maintained field offices in Germany and abroad staffed by Abwehr officers. In Germany and occupied countries these field offices were referred to as Abwehrstellen (Asts) with branches thereof called Nebenstellen (Nests); in neutral countries the Abwehr office was called a Kriegsorganisation (KO) and usually acted under cover of the diplomatic mission. Organizationally the field stations reproduced the functional division at headquarters. Both headquarters and the field stations recruited, trained, and dispatched espionage agents for missions abroad. While in theory there was a rough geographical division of responsibility between the various Asts, in practice there was a great deal of overlapping. Thus while Ast Hamburg, and its subsidiary Nest Bremen, had primary responsibility for espionage against the United States there was nothing to prevent Ast Cologne or KO Spain from sending an agent to this country if it happened to recruit one it believed well fitted. This factor alone led to a good deal of confusion and inefficiency in the operations of the Abwehr. Personnel of the Abwehr included officers of the Army, Navy, and Air Force, both active and retired or reserve, and civilians recruited and commissioned directly.

Side by side with the Abwehr there existed another intelligence agency–the Sicherheitsdienst (S.D.). Originally the security and intelligence service of the Nazi Party, it came to play a more and more dominant role as an intelligence organ of the Reich until eventually it gained control over the Abwehr itself. In September 1939 the S. D. was brought together with the various police agencies of the State, including the Gestapo, to form the Reichssicherheitshauptamt (R.S.H.A.) or Central Security Service of the Reich. Through one section of the latter–Amt VI–the S.D. soon developed an interest in foreign intelligence and began dispatching its own agents abroad. At first it limited itself to political intelligence, but as the war developed it gradually extended its interests to economic and military matters, and by January 1944 was running its own espionage networks in Spain, Argentina, and elsewhere. The officials of the S.D. were virtually all members of the Nazi Party S.S.

As one phase of the rivalry between the Wehrmacht and the S.S., and also because of increasing annoyance with the failure of the Abwehr, there was a long campaign by the R.S.H.A., and particularly [Heinrich] Himmler and [Ernst] Kaltenbrunner, to gain control of the Abwehr. This was successful in the spring of 1944 when the Abwehr was finally taken over by the R.S.H.A. Some of its functions were handed over to Amt VI and Amt IV (the Gestapo) but the majority, as well as most of the personnel, were retained in a new section known as the Militaerisches Amt. Theoretically on a par with the other sections of the R.S.H.A., the MilAmt came more and more under the domination of Amt VI; after July 20, 1944, [Walter] Schellenberg, head of Amt VI, took over the MilAmt as well as a result of the execution of Col. Hansen, its former chief, for his part in the plot against Hitler's life. Thus during the last year of the war the R.S.H.A. dominated the whole field of German intelligence. In the earlier part of the war most of the agents met with abroad represented the Abwehr, but towards the end they were almost sure to be S.D. agents.

As early as 1936 Korvetten-Kapitaen Pheiffer, a veteran of the German Navy of World War I, who had returned to active duty as an Abwehr officer in 1935, was collecting information from the United States of interest to the German High Command. Pheiffer was in charge of the naval section of Nest Bremen and as such in a position to establish close contacts with the extensive German shipping interests centered in that port. At first he worked through the "Aussenhandelstelle," or foreign trade office, where all German businessmen going overseas were registered, interviewing returning travelers on their return for any interesting observations they might have made, especially in foreign ports. From, these casual contacts Pheiffer subsequently recruited agents for the express purpose of seeking information abroad. At the same time he was enlisting the assistance of officers of the Merchant Marine both in reporting their own observations and seeking information from contacts in foreign ports whose reports they would turn over to Pheiffer. The latter has stated the German intelligence files had become so out of date during the 1920s and early 1930s that when the period of rearmament began it was necessary to seek information of all types from abroad–much of it by no means secret–in order to compile up-to-date data. Nevertheless, Pheiffer was particularly interested in new technical developments in the fields of ship design, armament, and special equipment.

It was through one of his volunteer agents on the liner Bremen that Pheiffer made contact with the notorious Dr. Griebl, who over a period of time supplied him with information on United States aircraft. This was also the period of Fritz Duquesne, Lili Stein, Gunther Rumrich and other German agents whose activities in the United States and arrests have received such wide publicity as not to warrant further discussion. Suffice it to say that while these and other agents who operated in this country before 1939 obtained information of some value to Germany, they did not succeed in obtaining vital secrets or in establishing a widespread espionage net that was able to continue into the war years.

After the outbreak of war in Europe, and particularly after the fall of France, it became of increasing importance for Germany to obtain intelligence on the nature and extent of equipment being sent to Great Britain, data on ship sailings and the war potential of the United States. Much of this was readily available from the press and other open sources in the United States to German diplomatic personnel. To supplement these sources and evade British censorship, the Abwehr established espionage networks in Mexico and other Latin American countries which relayed information from the United States to Germany by radio and other clandestine communications.

Among the most active of these was a ring in Mexico headed by Georg Nicolaus. Nicolaus, whose activities extended from 1940 to his arrest in the spring of 1942, was a competent individual. He had served with distinction in the Germany Army in World War I, spent many years in Colombia, and returned to Germany in November 1938. In January 1939, he was re-commissioned in the Army and assigned to Ast Hanover of the Abwehr. Late in 1939 he was ordered to Mexico to organize an espionage network. During his 2 years of activity in Mexico, Nicolaus organized an extensive network which maintained contact with other groups in South America and attempted to obtain information from the United States. While technical data from United States publications was extracted or photographed and some general information obtained from contacts in the United States, again there is no evidence that Nicolaus was successful in laying his hands on any vital military secrets. He was successful in leaving behind the nucleus of an organization which was able to maintain some activities throughout the war, although this was of little value to the enemy other than its nuisance value in occupying the attention of United States counter-intelligence agencies.

During this same period–between the outbreak of war in Europe and Pearl Harbor–the Abwehr succeeded in establishing a number of espionage networks in South America. These were centered in Brazil, Chile and Argentina, with ramifications in other countries. Until their liquidation, two groups in Brazil, headed respectively by Albrecht Gustav Engels and Nils Christian Christensen, were the most important and successful. Through organizations in Brazil itself, staffed by members of the well-entrenched German colony, information was collected on British shipping and forwarded by clandestine radio to Germany. Similar information from the River Plate region collected by agents in Argentina was relayed through the Brazil stations. The Brazil group also acted as relays for information of a more general nature, including intelligence originating in the United States, forwarded by such agents as Nicolaus in Mexico, Walter Giese in Ecuador, and the so-called PYL group in Chile. The group also had its own contacts on ships between the United States and Brazil. Through use of channels along the West coast of South America and connections with Europe via clandestine radio and the Lati airline, these scattered but interrelated groups were able to escape British censorship and maintain safe and reasonably rapid contact with Abwehr stations in Hamburg, Cologne and Berlin.

During 1940 and 1941 these groups must be credited with accomplishments which were probably of considerable value to Germany. Not only did they forward a quantity of basic economic data useful to Nazi analysis, but the shipping information supplied resulted in the loss to submarines of British and Allied ships. It is of interest that Nicolaus, Engels, and Christensen were all sent out by Group I (Wi) of the Abwehr (economic espionage), but as the war progressed their activities became more and more concentrated on naval and maritime intelligence. In general this was the most successful period of German espionage in the Western Hemisphere; after Pearl Harbor the Abwehr was never able to produce intelligence on the same scale.

The activities of these espionage groups in Latin America had not gone unnoticed by United States and British counter-intelligence agencies, but prior to Pearl Harbor there was little that could be done about them. During the early months of 1942 active steps were taken to correlate this information, identify those agents who were still unknown, and persuade local police authorities to arrest, intern, or deport them. As a result of these efforts the leaders of the Brazilian rings were arrested in March 1942 and Germany was never again successful in establishing an effective espionage service in Brazil. Prior to their liquidation, however, the Brazilian groups had made strenuous efforts to obtain military information from the United States. One example was the recruiting of a Brazilian Air Corps officer, who was coming to this country on an official mission under the auspices of our Military Attache to visit a number of aircraft factories. Fortunately, the Office of Naval Intelligence learned of this officer's connections shortly before his departure and his trip was canceled.

In most other Latin American nations, pressure from the United States succeeded in eliminating the most dangerous German agents by mid-1942. This success was tempered by continued toleration of active German espionage on the part of Argentina and Chile. In both countries Axis agents drew their support from large resident German colonies with strong local connections, from the continuance of diplomatic relations until a relatively late date, and from the complaisance of local officials.

After the breakup of the Brazilian groups, the organization in Argentina became the most important in South America. Between January 1942 and the spring of 1945 the German espionage network in Argentina went through a number of changes some of them forced by the arrest or exposure of its agents, but was always able to maintain a nucleus from which to build anew and to continue forwarding information to Germany.

During 1942 the dominant figure was Capt. Dietrich Niebuhr, the Naval Attaché, who had as his two principal assistants Hans Napp and Ottomar Mueller, and also enlisted the services of certain individuals who had escaped from Brazil at the time of the arrests there. The activities of Niebuhr and his immediate assistants were exposed in a note handed the Argentine Government by the United States Ambassador late in 1942 and a reorganization became necessary. This was accomplished by Gen. Friedrich Wolf, the Military Attache, and Johannes Siegfried Becker, an S.D. officer sent clandestinely to Argentina from Germany in January 1943. These two had at their disposition, both for personnel and funds, agents connected with the earlier groups still at large, the facilities of the German Embassy, German firms, Spanish shipping circles, and Argentine nationalists. From these diverse elements Wolf, and more especially Becker who was an extremely able individual, succeeded in weaving a net which had threads running into Uruguay, Paraguay, Chile, and even Mexico, and maintained fairly regular communication with Germany by radio and courier.

As a result of the arrest by the British of Osmar Alberto Hellmuth, an agent on his way to Germany from Argentina, in late 1943, information on the espionage activities of this group was furnished the Argentine Government which precipitated the rupture of diplomatic relations and the arrest of some of the most active agents. Becker survived this crisis. Within a couple of months he had his organization functioning again and in June 1944, received assistance from Germany in the form of two agents landed clandestinely on the coast of Argentina from an auxiliary yawl which had crossed the Atlantic from the French coast. The network suffered further losses from arrests in August 1944, but was able to continue some activities until the very end of the war.

Closely connected with the successive groups in Argentina, there existed until February 1944 an active German espionage organization in Chile. Mention has already been made of the PYL group which was active before Pearl Harbor and maintained contacts in all the West Coast South American countries as well as with the German groups in Brazil and Argentina. This group, under the control of Ludwig von Bohlen, Air Attache of the German Embassy, received assistance from numerous individuals and firms among the large German colony in Chile. As a result of information collected by United States counter-intelligence agencies and furnished the Chilean Government by the State Department, a number of the more active agents of this group were arrested in the fall of 1942. Enough escaped, however, to permit von Bohlen to rebuild another network, known as the PQZ group. When von Bohlen was repatriated late in 1943, this group was sufficiently well-organized so that he could leave it, as well as a large sum of money and equipment, in the hands of Bernardo Timmerman, who carried it on until his arrest in February 1944.

To supplement both his own organization in Argentina and the PQZ group, Johanns Siegfried Becker established a Sicherheitsdienst network in Chile early in 1943. This was under the leadership of Heinz Lange, a veteran of German espionage in Brazil and Paraguay, assisted by Eugenio Ellinger, whom Becker sent to Chile in April 1943. These two organizations, which worked closely together, maintained contacts in Peru and Bolivia. Most of their information was forwarded to Germany via Buenos Aires, although some was sent direct via short-wave radio. As a result of widespread arrests by Chilean police in February 1944, the espionage rings in Chile were effectively smashed–not, however, before some of their members escaped to Argentina where they continued their activities.

From the above it will be seen that the Germans succeeded in maintaining an espionage organization in South America, and communications between it and Germany, throughout most of the war. In this they were assisted by local elements in both Chile and Argentina, and especially by Spanish officials and members of the crews of Spanish ships who provided continuous courier facilities.

The question may well be asked, what and how valuable was the information these agents collected and forwarded to Germany? This question can only be answered with the reservation that we can never be sure that we have the whole answer. We do know a certain amount. Much of the information was of a general nature relating to industrial production in the United States, political and economic trends, labor disputes, and exports of raw materials from Latin America. These data were not obtained by "Mata Haris" from secret sources but from the careful perusal of thousands of United States publications, both general and technical, and from systematic contacts with Latin American individuals, both official and private, who were in a position to obtain information about the United States. The results were not dramatic, but they provided the raw material which any intelligence agency needs to formulate its picture of the enemy.

Aside from this general information, there was some of more direct naval interest. The Chilean group, especially concentrated on reporting the movements of United Nations vessels along the West Coast, together with data on the antisubmarine equipment and armament of both merchant and naval vessels. Late in 1943 a report was sent to Germany from Chile, via Argentina, giving details of United States naval gunnery practice and data on certain types of torpedoes. This is believed to have been obtained either from Chileans who visited United States naval vessels, or from observations of gunnery exercises held aboard a United States cruiser off Callao in the summer of 1943 for the benefit of the President of Peru and a large party of Peruvian officials. Similarly, in December 1943, one of the German agents in Chile obtained from a Chilean Air Force officer, who had spent 9 months training at the Naval Air Station, Corpus Christi, technical details of United States aircraft construction and performance and data on naval flight instruction and training accidents.

The Germans did not limit their attempts to obtain information from the United States to the establishment of espionage nets on the periphery. Throughout the war attempts were made to establish agents within the United States itself. Speaking generally, it can be reported that these efforts failed. In most cases the agents were either apprehended before they could commence activities, or their operations were sufficiently well controlled to neutralize them. The reasons for their failure ranged all the way from carelessness–as in the case of Werner Janowski, an agent landed on the coast of [southern shore of the Gaspe Peninsula, Quebec] Canada [by U-518] early in November [9 Nov.] 1942, who was caught within a few hours through his stupidity in throwing away a box of Belgian matches in a hotel room and otherwise arousing the suspicions of civilians–to voluntary surrender on the part of the agent. Two of the eight saboteurs who landed in June 1942 gave themselves up to the Federal Bureau of Investigation and thus precipitated the arrest of the others. [On 13 June 1942, 4 agents were landed from U-584 on Amagansett, Long Island, New York; and on 17 June 1942, 4 agents from U-202 were landed on Ponte Vedra Beach, south of Jacksonville, Florida. A subsequent military trial of the 8 captured agents resulted in 6 death sentences, one life imprisonment and one 30-year sentence. On the recommendation of the Justice Department, President Truman granted executive clemency on condition of deportation to the two surviving agents who were deported to the American Zone of Germany in 1948].

Most of the cases of German espionage agents in the United States have received such wide publicity in the press that it is unnecessary to discuss them in detail. Mention of a few of them will serve to indicate that there were continued, if sporadic, attempts, on the part of Germany to place such agents. While the saboteurs' and Janowski's cases were the first to attract general attention, they were not the first agents to operate in the United States during the war. During the latter part of 1943 and early 1944, the Federal Bureau of Investigation announced the arrest of four groups of agents who had been operating independently for a considerable length of time. Ernest Lehmitz, Grace Buchanan-Dineen, and Wilhelm Albrecht von Rautter had all been recruited by the Abwehr in Europe between 1939 and 1941 and returned to the United States before Pearl Harbor. They surrounded themselves with a few assistants or subagents and forwarded reports in secret writing on shipping, war production, and other military information to cover addresses in neutral countries in Europe. The existence of all these agents first became known through Allied censorship, largely because of their use of cover addresses which were already compromised; and while in some cases it took long and painstaking research and the comparison of thousands of handwriting samples to identify them and their confederates, their reports to Germany were under the control of United States counter-intelligence agencies from a fairly early date in their active career.

The neutralization of these agents should not be interpreted as a sign of their incompetence or that of their Germany masters– except insofar as the furnishing of the same cover addresses to various agents was careless. Rather the fact that Lehmitz and von Rautter were able to live and operate in the United States in wartime for over 2 years without detection, must impress one with the need for constant vigilance, while their ultimate identification is a lesson in the relative importance of painstaking research and checking versus more melodramatic methods of counter-intelligence.

The arrests of its agents made in 1943 and early 1944 did not discourage German intelligence from sending further agents to the United States. Among the survivors of a submarine [U-1229] sunk off the coast of Maine in the summer of 1944 [on 20 August] was one Oscar Mantel, who was to have been landed on the Maine coast in order to establish himself as an agent in this country. He was an experienced intelligence agent with a history of activities in Spain and France and he had received considerable specialized training for his mission. In November 1944, the R.S.H.A. tried again. This time [on 29 November] a submarine [U-1230] succeeded in putting ashore William Curtis Colepaugh and Eric Gimpel, who made their way to Boston and New York. The former was a maladjusted American who had jumped ship in Lisbon and offered his services to the Germans, while the latter had been repatriated to Germany from South America. Within a month of his arrival, and after spending a good share of the funds advanced him, Colepaugh had surrendered. Then as a result of the interrogation of Colepaugh, Gimpel was arrested before he could begin to discharge his mission. [They were found guilty and sentenced to death in a military trial, but President Truman subsequently commuted the sentence.] As far as is known this was the last attempt of German Intelligence to send agents to the United States during the war; although as late as September 1945 a German who had been trained for a mission to the Western Hemisphere, and who was attempting to reach South America under false papers, was removed from a Spanish ship at Trinidad.

In addition to employing agents resident in the Western Hemisphere, the Germans utilized members of the crews of Spanish and Portuguese ships to observe shipping in the United States ports and to report on convoys sighted at sea. These seamen were also used to buy numerous American magazines which were then studied in Lisbon or clipped for use in Germany. From these sources, which represented exploitation of perhaps unavoidable loopholes in United States security rather than positive espionage, the Germans obtained information of over-all intelligence value, but little of immediate operational significance.

Throughout the war the Germans sought military, political and economic information of any and all types, and the broad assignments given agents may well be one reason for the failure to obtain specific data of high quality. At the same time, certain subjects received special emphasis. Among these were data on aircraft production and types, and information on anti-submarine devices. Beginning in late 1942 or early 1943 the Germans realized that the success of their submarine arm, in which they placed so much hope, was threatened by Allied anti-submarine devices and techniques, and information on these became the priority intelligence requirement and remained so until the end of the war. The information was sought from all the sources discussed above and in the neutral countries of Europe as well. Fantastic sums were offered on the Lisbon espionage market–and were sometimes paid for reports invented by the agents themselves. It is a source of satisfaction that interrogation of German intelligence and naval officials indicates that they never succeeded in getting the vital information.

In conclusion one may speculate as to the reasons why the German intelligence services failed to produce results more in keeping with the effort expended. The first reason seems to be over-organization, with conflicts and duplication between the Abwehr and R.S.H.A. and within the two organizations themselves. The Abwehr was further handicapped by bureaucracy, lack of initiative, and corruption on the part of many of its officers, who were lukewarm Nazis at best and regarded a berth in the Abwehr as an opportunity to avoid service on the Russian front. By contrast the R. S. H. A. tended to be aggressive and imaginative, but it suffered from lack of experience and inability to evaluate information objectively. The personnel of both services was poorly chosen. The comment has often been made by Allied counterintelligence agencies that most German agents were of low grade and quality. The fault appears to have been with the initial recruiting and not with the training, although this was sometimes superficial.

Of course in spite of these weaknesses, the constant attention of the Allied agencies was required to prevent the Germans from getting information which might have been of immense value to them. Our experience showed that passive security measures, while essential, are not enough. There must be constant active counter-intelligence, in the form of both research and field work and a coordination of the two, directed toward increasing our knowledge of the enemy's intelligence organization, methods, capabilities and personnel.

Bishop, Eleanor C. Prints in the Sand: The U.S. Coast Guard Beach Patrol During World War II. Missoula MT: Pictorial Histories Publishing Co., 1989. [The landing of 4 Abwehr agents on Amagansett, Long Island, New York, from U-584, and 4 agents on Ponte Vedra Beach, south of Jacksonville, Florida from U-202 in June 1942, are described on pp. ix-x; the November 1944 landing of agents Gimpel and Colepaugh in Maine from U-1230 is described on pp. 30-31.].

Blair, Clay. The Hunted, 1942-1945. vol. 2 of Hitler's U-Boat War. New York: Random House, 1998. [The unsuccessful mission in August 1944 to land an agent from U-1229, the agent's capture after the sinking of the submarine, and the Navy's decision to treat him as a prisoner of war rather than turn him over to the FBI is described on p. 644. For the story of the two agents landed in November 1944, see pp. 646-647.].

____. The Hunters, 1939-1942. vol. 1 of Hitler's U-Boat War. New York: Random House, 1996. [For the landing of agents in June 1942, and their subsequent fate, see pp. 603-606. Also mentioned is the arrest of 14 friends and relatives of the agents, and the conviction of 10 of them. President Truman later commuted the sentences of the friends and relatives.].

Breuer, William. Hitler's Undercover War: The Nazi Espionage Invasion of the U.S.A. New York: St. Martin's Press, 1989. [See the appendix on pp.321-324, "Espionage Agents Convicted in the United States, 1937-1945."].

Breuer, William. Hitler's Undercover War: The Nazi Espionage Invasion of the U.S.A. New York: St. Martin's Press, 1989. [See the appendix on pp.321-324, "Espionage Agents Convicted in the United States, 1937-1945."].

____. Top Secret Tales of World War II. New York: John Wiley & Sons, 2000.

Cohen, Gary. "The Keystone Kommandos." Atlantic Monthly 289, no.2 (Feb. 2002): 46-59. [Includes two photos of the military tribunal, mug shots of the eight prisoners as well as short biographies, information on the execution and burial of the condemned, and an anecdote about George Dasch's later years and his friendship with Charlie Chaplin.].

Conn, Stetson, Rose C. Engelman, and Byron Fairchild. Guarding the United States and Its Outposts. Washington DC: Office of the Chief of Military History, 1964. [For the June 1942 landings see pp. 99-100.].

Dasch, George John. Eight Spies Against America. New York: R.M. McBride Co., 1959.

Farago, Ladislas. The Game of Foxes: The Untold Story of German Espionage in the United States and Great Britain During World War II. New York: David McKay Company, 1971.

Gimpel, Erich with Will Berthold. Spy for Germany. London: Robert Hall, 1957.

Hadley, Michael L. U-Boats Against Canada: German Submarines in Canadian Waters. Kingston and Montreal, Canada: McGill-Queen's University Press, 1985. [Includes the story of Werner Alfred Waldmar von Janowski who landed from U-518 in Canada on 9 Nov. 1942, as well as the story of the unmanned German weather station established by U-537 in northern Labrador on 22-23 October 1943.].

Hilton, Stanley E. Hitler's Secret War in South America 1939-1945: German Military Espionage and Allied Counterespionage in Brazil. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University, 1981.

Jong, Louis de. The German Fifth Column in the Second World War. Chicago IL: University of Chicago Press, 1956.

Kahn, David. Hitler's Spies: German Military Intelligence in World War II. New York: Macmillan, 1978. [The story of the November 1944 landing of two agents, including a map of their landing place in Frenchman Bay, is in Chapter 1, "The Climax of German Spying in America," pp. 2-26. Useful footnotes are on pp. 553-554].

Lardner, George, Jr. "Nazi Saboteurs Captured." The Washington Post Magazine (13 Jan. 2002): 12-16, 23. [Includes photos of the eight saboteurs landed in June 1942, information on their trial before a military tribunal, the execution of six of them by electric chair, and the fate of George Dasch after his return to Germany in 1948.].

Morison, Samuel Eliot. The Atlantic Battle Won, May 1943 - May 1945. vol. 10 of History of United States Naval Operations In World War II. Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1960. [ See pp. 326-327 for brief information on the unsuccessful attempt to land Mantel from U-1229; and pp. 330-331 for the landing of agents in November 1944.].

____. The Battle of the Atlantic, September 1939 - May 1943. vol.1 of History of United States Naval Operations In World War II. Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1947. [See p. 200 for brief information on the June 1942 landings.].

Noble, Dennis L. The Beach Patrol and Corsair Fleet. Washington DC: Coast Guard Historian's Office, 1992. [See pp. 8-11 for the story of the agents landed in June 1942 on Long Island.].

The Oxford Companion to World War II. New York: Oxford University Press, 1995. [See "Latin America at War" for a summary of Latin American activities not emphasizing espionage; and "Spies," which includes a section on German intelligence in the Western Hemisphere.].

Rachlis, Eugene. They Came to Kill: The Story of Eight Nazi Saboteurs in America. New York: Random House, 1961.

Whitehead, Don. The FBI Story. New York: Random House, 1956. [For the landing of German agents in 1942 and 1944, see pp. 199-206.].

Wighton, Charles and Gunter Peis. Hitler's Spies and Saboteurs: Based on the German Secret Service War Diary of General Lahousen. New York: Henry Holt and Company, 1958. [Lahousen was head of the Abwehr's Abt. II, which was responsible for sabotage.].

Willoughby, Malcolm F. The U.S. Coast Guard in World War II. Annapolis MD: United States Naval Institute, 1957. [The landings of German agents is discussed on p. 46, within a chapter on the Beach Patrol.].

Read the whole story

· · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · ·

- Print publication year: 2005

- Online publication date: February 2010

4 - Nazi Espionage: The Abwehr and SD Foreign Intelligence

- Richard Breitman, American University, Washington DC, Norman J. W. Goda, Ohio University, Timothy Naftali, University of Virginia, Robert Wolfe, U.S. National Archives and Records Administration

- Publisher: Cambridge University Press

- https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511618178.009

- pp 93-120

Summary

During the war, the Allies viewed German intelligence as a military and political weapon that they could neutralize if they knew enough about it. At the end of the war, Nazi spies, saboteurs, and intelligence officials might have helped diehard Nazis resist the Allied occupation of Germany or prepare for a future struggle, so even in the postwar period the Allies tried to capture German intelligence personnel and to understand the structure of German intelligence organizations. British and American intelligence officials, often working together, were able to fill gaps in their knowledge.

The IWG declassified a small quantity of new Allied material about small German intelligence organizations, such as the Research Office (Forschungsamt), an interception, wiretapping, and decoding service under the nominal supervision of Hermann Goring. The Research Office monitored some of the most sensitive internal Nazi operations, wiretapping uncooperative Catholic priests and Protestant pastors who were or were going to be persecuted. Foreign diplomats in Berlin were another regular target for wiretaps. British and American intelligence paid greater attention to the Abwehr, SD Foreign Intelligence, and the Gestapo.

The Abwehr

Allied officials initially thought of the Abwehr as the premier German intelligence service. The Abwehr was a top-heavy and generally inefficient military intelligence organization of more than twenty-one thousand officials in 1941, not including informants and other sources. Two particularly good studies of the Abwehr have enriched our understanding of this organization, but both of them were written decades ago.

Read the whole story

· ·

U.S. indicts 54 in Aryan group

Federal investigation targets supremacists based in stateby Debra Hale-Shelton | Today at 4:03 a.m. | Updated February 13, 2019 at 4:03 a.m.1COMMENT

Follow

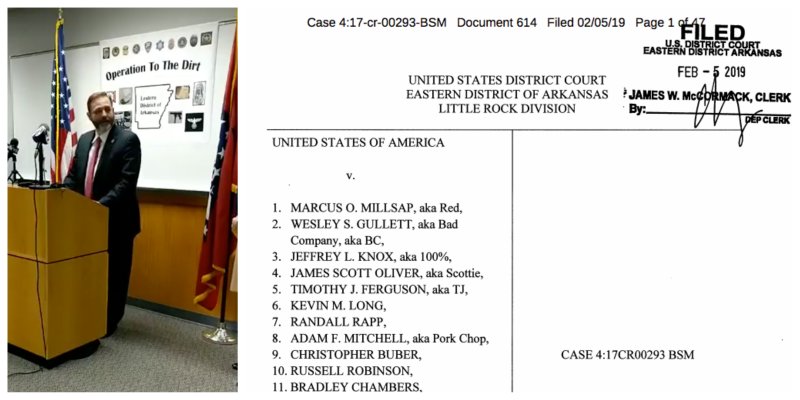

At left, U.S. Attorney for the Eastern District of Arkansas Cody Hiland speaks at a news conference Tuesday in Russellville. At right, a screenshot of the first page of an indictment in an investigation into an Arkansas white supremacy group.

RUSSELLVILLE -- The New Aryan Empire, an Arkansas-based white supremacist group, has committed attempted murder, kidnapping and maiming in support of its organization and drug-trafficking operation, federal prosecutors said Tuesday in announcing the indictment of 54 of the group's roughly 5,000 members.

The indictment resulted from an investigation dubbed To The Dirt, which began in 2016 when federal authorities assisted the Pope County sheriff's office in a murder case involving members of the supremacist group that began as a prison gang in 1990 and has since expanded outside the prison and to neighboring communities and states.

Crime Updates

Stay up to date with the latest Arkansas crime.

The superseding indictment, returned Feb. 5 and publicly released Tuesday, follows the U.S. attorney's office announcement in 2017 that it had indicted 70 people in the same operation on drug-trafficking and firearms charges.

The new, superseding indictment charges 17 of the 54 defendants with crimes under the Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations Act, known as RICO, and the Violent Crimes in Aid of Racketeering statute, called VICAR.

U.S. Attorney Cody Hiland said the indictment represents "the first RICO / VICAR case brought in 15 years."

"RICO focuses specifically on racketeering and allows members of the organization to be held responsible for the acts of the other members," Hiland said at a news conference with other federal, state and local law enforcement representatives.

"It's a powerful tool that we will not wait ... another 15 years to utilize both for violent crimes and for public corruption" in white-collar cases, Hiland said. "There'll be more in the coming weeks and months, and it's going to be a tool we rely on significantly as we move forward."

Assistant U.S. Attorney General Brian A. Benczkowski said the New Aryan Empire associates stand accused of maintaining "their criminal enterprise by engaging in multiple acts of violence -- including kidnapping and attempting to murder one informant, and stabbing and maiming two others suspected of cooperating with law enforcement."

An inmate at the Pope County jail in Russellville founded the New Aryan Empire, which Deputy U.S. Assistant Attorney General David Rybicki described as "a violent and highly structured criminal enterprise" associated with other white supremacist groups such as the Aryan Brotherhood.

Rybicki called the New Aryan Empire "reprehensible" for its Nazi-like views and said "one particular chilling" allegation involved the maiming of a suspected informant's face with a knife.

The term "To The Dirt" refers to the New Aryan Empire's slogan referring to a rule that members must remain in the group until they die, Hiland's office said in a news release.

Thirty-five of the 54 defendants, most of whom are residents of Pope and Yell counties, were in state or federal custody as of Tuesday afternoon; three were being arraigned in federal court; and 16 were previously released on bail.